Rumblings of what would become The Protestant Reformation started in the 14th century with men and woman noticing something wrong in the Church. From community priests to the pope himself, corruption and abuse of power ran rampant, and it intimately affected the lives of millions of people across Europe. Drastic reforms were needed.

Over the span of about 2 centuries, courageous men and women held to their conviction that eternal salvation was secured only by faith in Christ by the grace of God, as revealed in Scripture, all for God’s glory. Reformers spoke this truth of Scripture to abusive church practices and warped church doctrine. This movement, called The Protestant Reformation, left the world forever changed.

Why Did the Protestant Reformation Happen?

In the early 16th century, a scholar named Erasmus objected to several issues in the Roman Catholic Church, which at the time was the entire Church. He saw four major discrepancies between what the Church was teaching and what Scripture actually taught.

1. Church leaders enjoyed lives of wealth and ease.

Erasmus wrote The Praise of Folly, which poked fun at the errors of Christian Europe. He reminded his readers that Peter said to Jesus, "We have left everything for you" (Matthew 19:27, Mark 10:28, Luke 18:28). But Folly boasts that thanks to her influence, "there is scarcely any kind of people who live more at their ease" than the successors of the apostles.

2. The Church refused to allow priests to marry.

Erasmus attacked Rome's refusal to let priests marry, although some lived openly with mistresses. He even denied that popes truly have all the rights that they claim.

3. The Church insisted on practices not required in Scripture.

The scholar also challenged practices not taught in Scripture such as prayers to the saints, indulgences, and relic-worship.

4. The Church’s Latin translation of the Bible contained errors.

Jerome finished translating the Old and New Testaments into Latin by 405 A.D. His translation was called the Vulgate, and it was the Bible of the Church for centuries. However, Jerome's translation had deficiencies.

Erasmus reconstructed the original New Testament as best he could from Greek texts and printed it. In a parallel column, he provided a new Latin translation. What is more – and this could have cost him his life – he added over a thousand notes that pointed out common errors in interpreting the Bible.

Like Jerome's translation, Erasmus' New Testament was not completely accurate either. He did not have access to the best manuscripts. But it was enough of an improvement that Martin Luther, William Tyndale, and other translators based their vernacular versions on it. Furthermore, they picked up Erasmus's calls for reform.

This content was adapted from “Erasmus Loaded the Reformation Cannon” by Dan Graves.

Early Protestant Reformers

While Erasmus was indeed a protester of many Church practices and teachings, others were likewise concerned and worked towards reform centuries before. In the 14th century, John Wycliffe and John Hus sparked reformation by preaching the gospel in the language of the people, not Latin.

- John Wycliffe

Wycliffe and his band of preachers, called Lollards, were concerned that the people of England were not hearing the word of God in the common tongue. He not only preached the Bible in the English language of the people, but he also sent out his Lollards across the land with evangelistic messages. This powerful movement was picked up by leaders on the continent.

- John Hus

One of those leaders was a Roman Catholic priest, John Hus. Hus ministered in Bohemia, the modern Czech Republic. In the tongue of the people, he explained advanced doctrines that he found in the Bible such as salvation by grace through faith in Jesus Christ. While Wycliffe and Hus were the morning stars of the Reformation, Martin Luther was the exploding nova of the Reformation.

This content was adapted from “What Is Protestantism & Why Is It Important?” by Dr. Michael A. Milton.

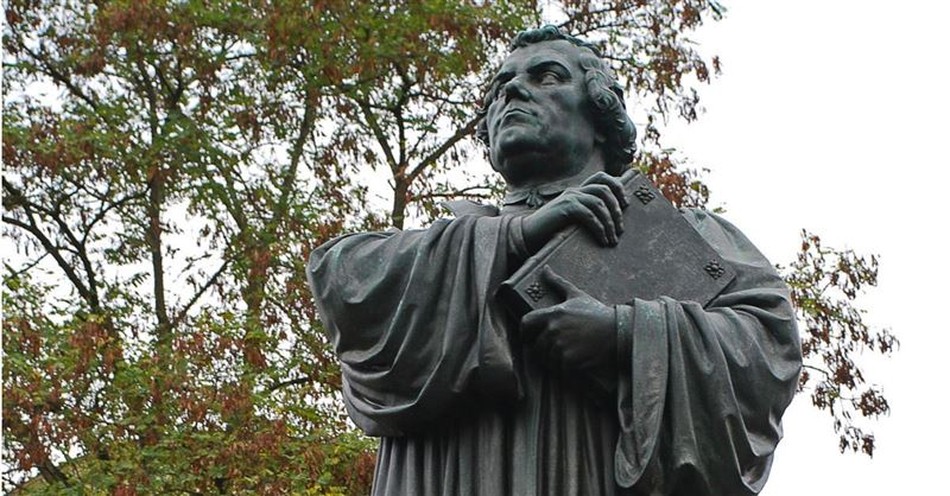

Martin Luther: A Key Player in the Protestant Reformation

In Martin Luther’s time, Pope Leo X was head of the Church. The Pope’s taste for extravagance drained the treasury in only eight years. But St. Peter’s Basilica needed to be rebuilt, so the pope offered indulgences in exchange for funds to rebuild the cathedral. Indulgences were letters of pardon which guaranteed forgiveness of sins. Luther saw this as a perversion of the gospel.

He was a pastor at the church in Wittenberg, Germany, and was so outraged that he wrote his now-famous 95 Theses and posted them on the door of the church, inviting scholars to debate the issue of indulgences. The printing press had recently been invented, so Luther's theses were printed up, and within weeks, copies were in demand and stimulating debate across Europe.

Within three years the pope issued a decree (a "papal bull") excommunicating Luther as a heretic. Emperor Charles V also condemned Luther, ordering him to be captured or killed on sight. But he was kidnapped and protected by Duke Frederick of Saxony.

Luther then poured his energy into studying, writing, and translating the New Testament into a German that everyone could understand. His ideas and writings spread across Europe like water from a burst dam. The Reformation could not be stopped.

This content was adapted from “Martin Luther: Monumental Reformer” by Dr. Ken Curtis.

John Calvin and the Protestant Reformation

Nearly two decades after Martin Luther drove the 95 Theses onto the door of a Catholic church in Germany, John Calvin was summoned to become a leader of the Protestant movement in Geneva, Switzerland. According to Christian scholars, Calvin had gone to Geneva to avoid the persecution of Protestants in France, and upon his arrival, he was astounded that people there knew of him.

He was recognized for a book he had written at the age of 27, titled Institutes of the Christian Religion, a work on Reformed theology still referenced today. Calvin was reluctant to guide the Protestant movement because of his youthfulness and inexperience. However, after some encouragement from notable leader Guillaume Farel, he became a “second generation” reformer. Both men’s portraits are now engraved into the Reformation wall in Geneva.

What are the Five Solas of the Protestant Reformation?

The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century changed Christianity forever. One of the enduring legacies are The Five Solas, which are five Latin phrases that emerged during the Reformation to summarize the Reformers’ theological convictions about the essentials of Christianity, based on Scripture.

1. Sola Scriptura (Scripture alone)

The Bible alone is our highest authority. This doesn’t mean that the Bible is the only place where truth is found, but it does mean that everything else we learn about God and his world, and all other authorities, should be interpreted in light of Scripture. The Bible gives us everything we need for our theology. (Romans 15:4, 2 Timothy 3:16-17)

2. Sola Fide (Faith Alone)

We are saved through faith alone in Jesus Christ. We are saved solely through faith in Jesus Christ because of God’s grace and Christ’s merit alone. We are not saved by our merits or declared righteous by our good works. (Luke 7:50, Romans 10:9, John 3:14-16, John 20:31)

3. Sola Gratia (Grace Alone)

We are saved by the grace of God alone. We can only stand before God by his grace as he mercifully attributes to us the righteousness of Jesus Christ and attributes to him the consequences of our sins. Jesus’ life of perfect righteousness is counted as ours, and our records of sin and failure were counted to Jesus when he died on the cross. (Ephesians 2:8, 2 Corinthians 5:21)

4. Solus Christus (Christ Alone)

Jesus Christ alone is our Lord, Savior, and King. God has given the ultimate revelation of himself to us by sending Jesus Christ (Colossians 1:15). Only through God’s gracious self-revelation in Jesus do we come to a saving and transforming knowledge of God (Acts 4:12). Because God is holy and all humans are sinful (Romans 3:23), neither religious rituals nor good works mediate between us and God. Hebrews 7:25 There is nothing by which a person can be saved other than the name of Jesus. His sacrificial death alone can atone for sin (1 John 2:2).

5. Soli Deo Gloria (To the Glory of God Alone)

We live for the glory of God alone. God’s glory is the central motivation for salvation, not improving the lives of people—though that is a wonderful by-product. God is not a means to an end—he is the means and the end. The goal of all of life is to give glory to God alone (1 Corinthians 10:31). As the Westminster Catechism says, the chief purpose of human life is “to glorify God and enjoy him forever.” Glory belongs to God alone because only he is worthy (Revelation 4:11, Psalm 145:3, Psalm 18:3).

This content was adapted from “The Five Solas - Points from The Past That Should Matter To You” by Justin Holcomb.

Significance of the Protestant Reformation

1. The Protestant Reformation birthed Protestantism and the Protestant faith.

The Protestant Reformation movement birthed the Protestant denomination, which at the writing of this article, includes nearly 1 billion people. The phrase “ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda” (the church reformed, always reforming) is an appropriate description of the heartbeat of the Protestant faith for a given church community as well as for the individual. The word is, of course, from the word “protest.” And while “protest” harkens back to Luther, Wycliffe, Hus, and others; the meaning of Protestant was, is, and will, no doubt, continue to be, an impulse in the Church for reform.

2. The Protestant Reformation inspired a “Counter-Reformation” within the Catholic Church.

Beginning with Pope Paul III, the first pope of the Counter-Reformation, Catholic Church leaders met for three conferences of The Council of Trent to attempt their own reform during the 16th century. To achieve reform, they responded to Protestant criticisms with clearly defined doctrines. Other results of the Council of Trent involved punishing corrupt clergy as well as setting regulations in place to avoid issues such as:

- Clergy living in luxury

- Clergy selecting family members to fill prestigious church roles

- Undertrained clergy

This content was adapted from “What Is Protestantism & Why Is It Important?” by Dr. Michael A. Milton.

Sources:

- Briannica.com, Counter Reformation, The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Briannica.com, Council of Trent, The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Christianity.com, Infamous Indulgence Led to Reformation, Dan Graves (2007).

- ChristianityToday.com, 405 Jerome Completes the Vulgate, (1990).

Photo Credit: Thinkstock/BMG_Borusse